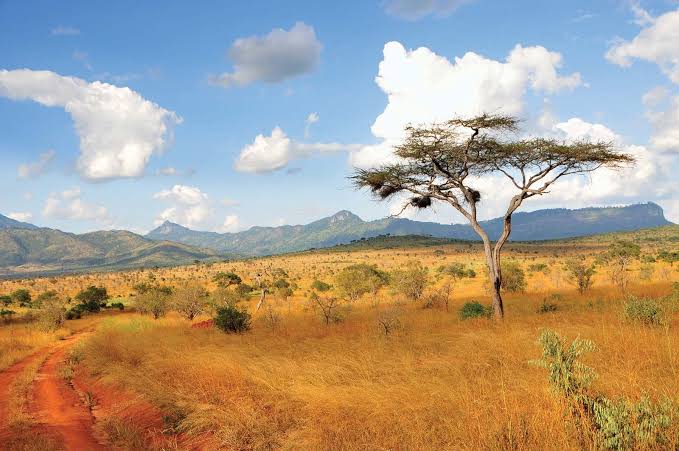

Kenya, often celebrated for its breathtaking landscapes, diverse wildlife, and vibrant cultures, also carries a history as rich and fascinating as its natural beauty. From early human settlements and thriving trade networks to the struggle for independence and nation-building, the history of Kenya is a story of resilience, adaptation, and unity in diversity.

Early Human Settlements

Kenya is sometimes called the “Cradle of Humankind” because some of the oldest human fossils were discovered here. The Great Rift Valley, which cuts across the country, has yielded archaeological evidence showing that early hominids lived in Kenya millions of years ago. Famous discoveries by the Leakey family in Olduvai Gorge and Lake Turkana confirmed Kenya’s role in human evolution.

These early inhabitants were hunter-gatherers, living in small groups and relying on stone tools. Over time, they developed more complex societies, paving the way for the communities that would later inhabit the region.

The Bantu and Nilotic Migrations

Around 2,000 years ago, Kenya became home to waves of migration.

Bantu-speaking peoples migrated from Central and West Africa into the fertile highlands of central and western Kenya. They brought with them iron-working, farming skills, and permanent settlement patterns. Communities such as the Kikuyu, Luhya, Meru, and Kamba trace their roots to this migration.

Nilotic-speaking groups, including the Maasai, Luo, Turkana, and Samburu, moved from the Nile Valley region. Many became pastoralists, herding cattle and moving across the plains in search of pasture.

Cushitic-speaking peoples, such as the Somali and Borana, settled in the northeastern regions, bringing with them camel herding and long-distance trade traditions.

These migrations shaped Kenya’s ethnic and cultural diversity, laying the foundation for the over 40 ethnic groups that live in the country today.

Coastal Trade and the Coming of Islam

Kenya’s Indian Ocean coast has long been a hub of international trade. By the first millennium AD, Arab, Persian, and Indian traders were sailing across the Indian Ocean to exchange goods with local communities.

Coastal towns like Mombasa, Lamu, and Malindi grew into thriving trade centers, dealing in ivory, gold, spices, and slaves.

This interaction led to the rise of the Swahili culture, a unique blend of African, Arab, and Persian influences. The Swahili language (Kiswahili), which is today Kenya’s national language, emerged from this cultural fusion.

Islam also spread along the coast, influencing architecture, education, and social practices. Mosques and coral-stone houses became defining features of coastal towns.

The prosperity of these trade centers attracted foreign powers, making the coast a contested zone for centuries.

Portuguese, Omani, and European Influence

In 1498, the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama arrived at the Kenyan coast, marking the start of European involvement. The Portuguese controlled coastal towns for nearly two centuries, building forts such as Fort Jesus in Mombasa.

By the late 1600s, however, the Portuguese were expelled by Omani Arabs, who established control and strengthened Islamic influence. Omani rule encouraged more settlement by Arab traders, who expanded the slave trade. Thousands of Africans were taken from Kenya and neighboring regions to work in plantations in Arabia and beyond.

By the 19th century, European powers, particularly the British, turned their attention to East Africa, driven by trade interests and the “Scramble for Africa.”

The Coming of the British

In the late 1800s, Britain established control over Kenya, initially through the Imperial British East Africa Company and later as a protectorate (1895) and colony (1920). The British introduced:

Railways: The building of the Uganda Railway (1896–1901) connected Mombasa to Kisumu, opening up the interior for trade and settlement. Indian laborers, brought to work on the railway, laid the foundation for Kenya’s Asian community.

Settler Farming: Large tracts of fertile land in the central highlands were taken from local communities and given to European settlers for commercial farming.

Taxes and Forced Labor: Africans were forced to work on settler farms through hut taxes and harsh labor policies.

Colonial rule disrupted traditional societies, dispossessed communities of land, and imposed foreign governance. However, it also introduced modern education, Christianity, and infrastructure that would later shape Kenya’s development.

The Rise of Nationalism and Resistance

Colonial exploitation and land alienation led to widespread discontent. Resistance began with local leaders like Koitalel Arap Samoei of the Nandi, who fought the British between 1895 and 1905. Other communities also resisted colonial intrusion through both warfare and diplomacy.

By the mid-20th century, organized nationalism emerged. Educated Africans demanded reforms, representation, and eventually independence. The most notable resistance came in the form of the Mau Mau rebellion (1952–1960), led largely by the Kikuyu but supported by other groups. Mau Mau fighters waged a guerrilla war to reclaim stolen land and demand freedom.

The rebellion was brutally suppressed, but it forced Britain to reconsider its colonial policies.

Independence and Nation-Building

On December 12, 1963, Kenya gained independence, with Jomo Kenyatta, a Kikuyu leader, as the country’s first Prime Minister (later President). The following year, Kenya became a republic.

Independence brought hope and challenges:

The government embarked on land redistribution, though not all grievances were resolved.

Efforts were made to unify Kenya’s diverse communities under the motto “Harambee” (pulling together).

Infrastructure, education, and healthcare were expanded to serve a growing population.

Kenyatta was succeeded by Daniel arap Moi (1978–2002), whose long rule was marked by both stability and controversies over corruption and authoritarianism. The push for democracy led to the introduction of multiparty politics in the 1990s.

Modern Kenya

Today, Kenya is one of Africa’s most influential countries, both politically and economically.

Economy: Agriculture, tourism, and technology (with Nairobi as a tech hub nicknamed “Silicon Savannah”) drive growth.

Culture: Kenya celebrates its diversity of over 40 ethnic groups while promoting unity through Kiswahili and national traditions.

Sports: The country is world-renowned for its long-distance runners, who have won countless global titles.

Politics: Kenya continues to face challenges such as ethnic tensions, corruption, and inequality, but it has also made strides in democracy and governance.

Kenya remains a key player in regional peacekeeping and international diplomacy.

Conclusion

The history of Kenya is a story of resilience. From its role as the cradle of humankind to the rise of ancient trade centers, from the struggles of colonization to the triumph of independence, Kenya has continuously adapted and grown. Its people have endured hardships, defended their land, and embraced change to build a modern nation.

Kenya’s journey shows how deeply history shapes identity, reminding us that a nation’s strength lies in its ability to honor the past while striving for a better future. Today, Kenya stands not only as a land of breathtaking beauty but also as a nation whose history inspires both its citizens and the world.

Comments (0)